Mobility in Sport: Beyond Flexibility and Into Function (Part 4: The Joint-By-Joint Approach, Length-Tension Relationship Change, Application & Stretching “Tightness”)

- Dec 27, 2025

- 15 min read

This final part of this 4-part blog series will conclude by shifting the discussion from theory into practice, exploring how concepts of mobility, stability, force production, and adaptation can be applied. The section aims to bridge the gap between understanding why mobility changes occur and how we can meaningfully develop mobility that transfers to performance, resilience, and long-term joint health.

The Stability vs Mobility Conundrum

It is well documented in the literature the fascinating interdependent relationship between mobility and stability - quite simply, one cannot exist without the other. Throughout this blog series we have clearly outlined what mobility is, but what do we mean by stability? Gray Cook (2003) defined stability as “the ability to control force or movement.”

A clear example of this interaction can be seen when examining hip flexion patterns. During a passive straight leg raise, an athlete may demonstrate excellent muscle extensibility, or mobility, of the hamstring muscle group or in hip flexion with the knee extended with only subtle amounts of posterior pelvic tilt at the end range. However, the same athlete may not be able to demonstrate this exact ROM during a standing variation of a similar task, for example, a single-leg RDL. As the nervous system detects a greater stability demand. In response, it often reduces available mobility in order to maintain equilibrium. This illustrates the constant interaction between mobility and stability, as well as the critical role of task specificity. Despite superficial similarities in joint action, the underlying demands of the task differ, and consequently the movement outcomes differ. The context and constraints under which a movement pattern or joint action is assessed can alter the expression of mobility and may therefore misrepresent an individual's true movement capacity.

Additionally, Cook (2011), in his more well-known book Movement, expanded on his earlier work, stating that “true authentic stability is about effortless timing and the ability to go from soft to hard to soft in a blink.” Here, Cook here alludes to what I believe is one of the most overlooked and crucial components of high performance: timing, or more specifically, subconscious sequencing. Possessing high levels of strength or peak force capacity is of little value if the coordination and sequencing of those forces are inefficient. This is often evident when observing elite movers – frequently not the biggest or strongest individuals, yet undeniably more efficient. Their advantage lies not in superior raw capacity, but in how efficiently they organise and express the physical qualities they possess.

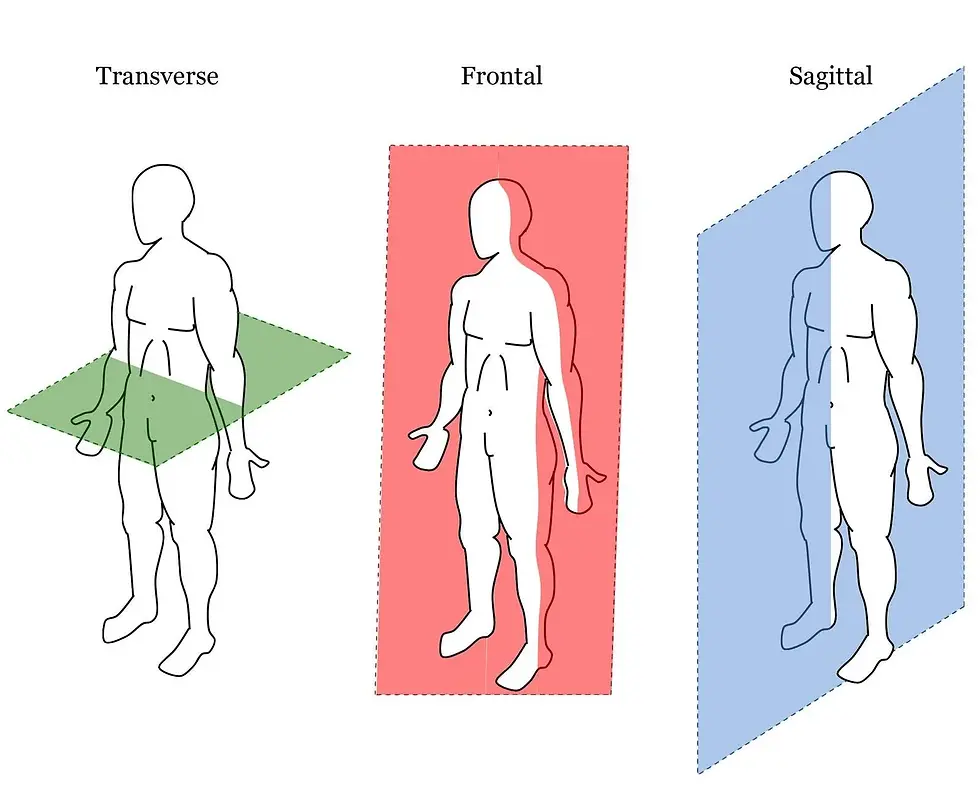

But what does all this have to do with mobility and accessing certain joint positions, you may ask? One useful framework that helps organise this discussion is the joint-by-joint approach, originally proposed by Gray Cook and Mike Boyle (2011). The model suggests that “the body is just a stack of joints. Each joint or series of joints has a specific function and is prone to predictable levels of dysfunction. As a result, each joint has particular training needs.” In other words, dysfunction often arises not from a lack of capacity in isolation but from a breakdown in how load and movement are shared and sequenced across the system or joint. Cook and Boyle suggested that joints throughout the body alternate between mobility and stability, with the scapula primarily contributing stability in order to allow effective mobility at the glenohumeral joint further up the chain. When this orderly sequence is disrupted, compensatory strategies frequently emerge, placing increased demands on neighbouring joints and segments. Crucially, this is not limited to the sagittal plane, and stability, or mobility, present in one plane does not necessarily mean stability in the other two planes (frontal & transverse).

As highlighted by Gary Ward, following tissue damage or injury, the traditional, outdated RICE (rest, ice, compression and elevation) protocol during the early stages of recovery may reduce pain symptoms and inflammation, but at what cost? Unintentionally this protocol can severely limit movement, and given the brain is highly adaptive and fundamentally task-driven, any persistent loss of movement options at one joint must be compensated for by neighbouring joint segments in order to achieve the desired outcome. Returning to our example of a torn rotator cuff tendon, an individual may initially experience pain at end-range shoulder flexion (180°), leading the nervous system to associate this pattern and position with pain and threat. Even once the tendon has structurally healed months later, the brain may continue to avoid this range, defaulting to alternative movement strategies to complete the task. In practice, this often manifests as a shift away from a strict scapulothoracic and glenohumeral-driven strategy and towards an excessive lumbar spine extension strategy to orientate the rib cage in such a way as to allow elevation of the arm overhead. Relating this to the joint-by-joint approach, the stable lumbar spine segment has now transitioned into a mobile segment in order to accomplish movement tasks requiring the shoulder flexion pattern, disrupting the logical, systematic joint-by-joint model. As Shirley Sahramann (2002) reiterated, increasing lumbar spine mobility has potentially dangerous long-term implications.

What I find especially interesting about this model are its assumptions. The framework suggests that the ankle should prioritise mobility and the knee stability, yet this generalisation could become problematic when applied across different sporting contexts. A particularly insightful perspective on this comes from Keenan Robinson, former USA Swimming S&C coach for Michael Phelps, who discussed how swimmers often present with demands that invert these traditional joint-by-joint expectations. Keenan suggests that in segments that in a land-based athlete require mobilisation, swimmers are already hypermobile. Further increasing mobility in these regions may therefore elevate injury risk. Instead, he argues that these areas would benefit far more from targeted stability work to ensure swimmers remain robust and successful in the water.

What we can take away from this is that mobility and stability are not opposing qualities but interdependent components of movement, governed by the nervous system and shaped by task demands. What appears to be a limitation in mobility can often be masked by insufficient stability, force tolerance or sequencing rather than true lack of ROM. Frameworks such as the joint-by-joint approach are useful with consideration of sport-specific demands and individual context. Increasing mobility in isolation with no appreciation of neighbouring joint segments may potentially exacerbate compensatory movement strategies and increase injury risk.

Sport-specific Adaptations & Length-Tension Relationship Shifts

Expanding upon our understandings of sport-specific demands and how these may shape our mobility, it is essential to consider how muscle length influences force production and our ability to access joint positions. Foundational work by Huxley (1954) and Gordon, Huxley and Julian (1966) demonstrated that muscle force production is highly dependent on muscle length – a concept now commonly referred to as the length-tension relationship. More specifically, they showed that sarcomeres – the fundamental contractile units arranged in series within myofibrils – produce maximal force when operating at near mid-range sarcomere lengths.

This principle was later reinforced by Rassier and colleagues (1999), who reported that muscles generate force at optimal sarcomere lengths, typically close to the mid-length range, while sub-optimal starting positions can reduce force production capacity. Functionally, this can be seen in kinetic testing using an isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP) within sporting settings. The lower limb joint angles adopted during the IMTP position the musculature responsible for initiating hip and knee extension in mid-range muscle lengths, or a mechanically advantageous position, where maximal force can be expressed into the ground.

However, a question that continually occupies my thinking is this: if most sporting activities are characterised by high-force eccentric muscle actions, and if we have already established that sufficiently demanding eccentric loading can induce sarcomeregenesis, what are the implications of this for an individual’s ability to access specific joint positions as well as maintain peak force production capabilities through all ranges within a joint?

To help illustrate my questioning, consider the example of a cricket fast bowler. Before progressing, it is important to acknowledge that there is currently no research (to my knowledge!) directly examining length-tension relationships in the specific manner discussed here. What follows is therefore grounded in applied practice, clinical reasoning and personal experience, using my own body as a vessel to explore the practical nuances of length-tension relationships in sporting movement. According to Orchard and colleagues (2017), fast bowlers are approximately 2.5 times more likely to sustain hamstring injuries compared to spin bowlers. While greater exposure to high-speed running undoubtedly contributes to this increased risk, sprinting volume alone, in my opinion, is unlikely to fully explain the discrepancy, but why?

During the delivery stride, the front leg hamstrings of a fast bowler are subjected to high magnitudes and rapidly applied eccentric loads at front foot contact (FFC), as the body braces prior to ball release. As described by Chalker et al. (2016), the hamstrings “act rapidly to decelerate the total body’s momentum” during this phase. More specifically, the proximal hamstrings play a critical role in eccentrically decelerating hip flexion as the torso is projected forward over a braced front leg at FFC, whilst the distal hamstrings are eccentrically challenged resisting knee flexion.

To illustrate this practically, my own recent hamstring kinetic testing revealed a clear length-dependent shift in force production capacity. During an isometric prone hamstring test on the NordBord, which biases the hamstrings towards longer muscle lengths at the distal end (full knee extension), as seen in fast bowling FFC positions, peak force output was biased towards my left, producing 376N compared to 345N on my right. However, when the hamstrings were tested closer to their inner ranges using a prone knee flexion test, with the hip extended and the knee flexed to 30°, a markedly different profile emerged. In this shorter muscle length position, peak force output dropped considerably to 170N on my left compared to 212N on my right, representing a near 20% asymmetry. Collectively, these findings suggest a shift in my left hamstrings force-producing capacity towards longer muscle lengths, with a reduction in force output at shorter muscle lengths. This pattern highlights how repeated exposure to high-force eccentric demands, such as those experienced during FFC in fast bowling, may drive length-specific adaptations within the muscle. Over time, these adaptations may alter the operating region of the muscle along the length-tension curve, influencing not only where force can be effectively expressed, but also which positions the tissue can tolerate under load. This further reinforces the notion that mobility, force production and tissue adaption cannot be considered in isolation, but rather as interdependent qualities shaped by the specific demands repeatedly imposed on the system.

As the SAID principle reminds us, specific adaptations are driven by imposed demands - quite simply, we are what we repeatedly do, or in this context, what we repeatedly expose ourselves to. In line with Cook and Boyle’s joint-by-joint approach, the goal is not simply to acquire ROM in mobile segments, but ensure the surrounding musculature of those mobile segments, remain mobile and produce appropriate levels of force through a wide spectrum of muscle lengths. Tim Caron’s (2022) concept of bandwidths captures this idea particularly well. Rather than attempting to force every individual into the same predefined movement standards, developing large bandwidths equips athletes with the capacity to express force across a variety of joint positions and muscle lengths, better preparing them to cope with the chaos of sport. Crucially, we must acknowledge that both sporting participation and weight-room training impose specific stimuli that shape how force can produced within tissues. The muscle lengths and joint positions we fail to expose and load are the very ones that gradually lose capacity. As Steffan Jones succinctly highlights, the role of weight-room is therefore not to replicate the sport, but to train what the sport does not - maintaining equilibrium in joint degrees of freedom, expand bandwidths and build robustness across the full spectrum of movement demands.

The “T” Word

By “T”, I am referring to tightness - a word that no doubt every coach, physio, personal trainer, chiropractor, sports masseuse hears on the daily from clients or athletes alike, but what does “tightness” actually mean? I will let you sit and think before continuing reading what you think “tightness” exactly means… Does it mean muscle soreness? Does it mean the muscle or muscle group has increased resting tone? Does it mean muscle tension? Does it mean muscle guarding is present in the muscle or muscle group due to previous trauma? Does it mean the muscle is being held in a shortened muscle state? Does it mean the muscle is being held in a lengthened muscle state? As highlighted by the brilliant mind of Austin Einhorn, an individual stating a muscle feels “tight” actually provides us with very little actionable information. The term is vague, non-specific and does not describe the underlying mechanism responsible for the sensation, yet is often used to justify blanket interventions without a clear understanding of what is actually occurring within the tissue or nervous system.

This is not to suggest that the sensation itself is invalid or incorrect - far from it. Having personally spent much of the last eight years experiencing persistent sensations commonly described as “tightness”, I can attest that these perceptions are very much real. The critical issue, however, is not whether the sensation exists, but how we interpret and respond to this information. This aligns directly with a point raised by Alex Wolf earlier in this blog series: if we have not clearly defined the ‘what’ (the specific quality we are attempting to change), which arises from understanding the rationale and ‘why’ behind what we are changing - then we cannot hope to create the optimal and appropriate environment required to drive meaningful and lasting adaption. Simply concluding that a muscle feels “tight” and therefore requires weeks of passive static stretching is a reductionist and dangerous approach that fails to respect the complexity of human movement. Adopting such a one-size fits all strategy neglects one of the most important considerations when working with humans: individualism.

To me this further highlights one of the biggest gaps within the rehab industry: the sheer amount of guesswork involved. At present, there appears to be an over-reliance on hypothesising casual relationships between findings without being able to truly confirm them. Yes, a VALD ForceFrame may identify a 30% asymmetry in hamstring peak force capacity, and yes, this may coincide with suboptimal backside mechanics observed during a 3D motion-analysis running assessment. However, we cannot definitively state that the sensation of “tightness” experienced in the lower back on the same side is a direct consequence of these findings. At best, we can reasonably speculate that a relationship may exist - but speculation is not certainty.

Ultimately, sensations of “tightness” represent only one piece of much large puzzle and require further exploration to understand why an individual experiences them. While these subjective reports form a valuable component of any assessment process, they should not be treated as definitive explanation. Prescribing the same static stretching routine to every individual is unlikely to address the underlying, root cause of an issue. Instead, deliberate and ongoing effort to ask “why” is required - exhausting all plausible contributing factors rather than adopting a reductionist, one-size fits all approach. Treating the human body as though we are all built and respond in the same way to stress and stimuli overlooks the fundamental differences of all humans.

Is Pre-Exercise Stretching Necessary?

One of the most common questions I get asked is, shall I stretch before I play sport as a part of my warm-up? My answer is consistently no - and not because stretching is inherently bad (if used in the correct situations it can be beneficial), but because the evidence overwhelming demonstrates that pre-exercise stretching, particularly static and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) modalities, compromises performance qualities critical for sport. A substantial body of research shows that acute stretching reduces force production, power output and neuromuscular activation, all of which are fundamental for both performance and joint stability.

Bradley and colleagues (2007) demonstrated that static (holding a position), ballistic (end-range repetitive bouncing) and PNF stretching all reduced jump performance, within static stretching producing the greatest decrement. While ballistic stretching had the least negative effect, it still impaired performance. The authors attributed these reductions to neural mechanisms, noting that static stretching can evoke myotatic reflex inhibition, while PNF stretching induced autogenic and reciprocal inhibition (refer back to Part 2!), both of which reduce neural drive to the stretched muscle.

In the influence of stretching duration was further clarified by Lima et al. (2019), who showed that static stretching lasting less than 60 seconds per muscle group resulted in minimal strength and power loss, whereas longer duration (>60 seconds) produced clear decrements in force and power. These longer stretches were associated with reduced voluntary activation, decreased EMG amplitude in the agonist musculature, and reduced musculotendinous stiffness - changes that collectively impair stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) performance and force expression. This raises a critical practical question: if meaningful increases in ROM require long-duration stretching, but those same durations acutely impair performance, what problem are we actually solving by stretching before exercise?

Marek et al. (2005) further demonstrated that both static and PNF stretching reduced peak torque (strength) and mean power output during leg extension, alongside reductions in muscle activation across both slow and fast contraction velocities. This inhibition compromises not only force production, but also the muscle's ability to stabilise joints effectively. When peak force and power are reduced, the same sporting task now requires a higher relative effort, accelerating local fatigue and increasing the likelihood of kinematic, technical breakdown and tissue failure. Barroso et al. (2012) extended these findings by examining strength-trained individuals and showed that all stretching protocols increased ROM (increased stretch tolerance), yet all reduced strength-endurance, with PNF stretching also reducing maximal strength. Despite increased flexibility, participants were able to perform fewer repetitions at 80% 1RM, suggesting that acute stretching compromises the ability to repeatedly produce force under load - an essential quality in most sporting situations.

These findings are reinforced by Shriver's (2004) review, in which 22 out of 23 studies reported that acute stretching before exercise provided no performance benefit and was instead detrimental to measures such as isometric force, isokinetic torque and jump height. Mechanistically, Magnusson (1998) proposed that both static and PNF stretching reduce force production is temporarily dampened, the muscle's ability to provide force closure and joint stability is compromised - an undesirable outcome immediately prior to sport.

In short, pre-exercise stretching may increase immediate passive ROM (increased stretch tolerance), but it does so at a cost of neuromuscular readiness, force production and joint stability. For activities that demand speed, power and robust control through wide, end-ranges, this trade-off is not only unnecessary but may also be counterproductive.

Post-Exercise Stretching?

But what about post-exercise stretching you may ask. Many individuals feel compelled to stretch after exercise or training under the assumption that it will reduce muscle soreness, accelerate recovery or relieve sensations of “tightness”. However, most evidence on the matter does not support these beliefs.

A systematic review by Herbert and colleagues (2011) reported that post-exercise stretching reduced delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) by only 1 point on a 0-100 scale, a change considered clinically meaningless. Similarly, Herbert and Gabriel (2002) concluded that stretching before or after exercises does not confer meaningful protection against muscle soreness or injury, with reported reductions in injury risk (approximately 5%) failing to reach any statistical significance. These findings are echoed by Andersen (2005), who demonstrated reductions in soreness of less than 2 mm on a 0-100mm scale, again described as having little to no practical relevance.

We can therefore deduce that sitting in a yoga pose for 3 minutes at the end of a training session is unlikely to meaningfully reduce muscle soreness or tissue damage incurred during high-intensity training. While post-exercise stretching may serve as a role in down regulating the nervous system - shifting from a sympathetic to a parasympathetic state - it should not be believed that post-exercise stretching will rid you of all your muscle pains and magically lower injury risk. Stretching may help you feel calmer and less tense due to breathing protocols usually associated with post-exercise stretching (ELDOA), but it will not miraculously eliminate soreness following five sets of supramaximal eccentrics simply because you held a downward dog for six minutes at the end of session. Just eat some nutritional food and get a good nights sleep.

Practical Application & Concluding Thoughts

Mobility is not flexibility. It is the active, controllable access to the joint positions your sport demands. Across this blog, the key message is that “good mobility” is not a universal score on the Beighton scale or FMS, but an individualised window of range that you can own under load and at speed. Range that exists passively, or only in low-threat conditions, has limited value if you cannot express force and control within it. Short-term stretching may change stretch tolerance and perception, but long-term, usable mobility is best built by exposing tissues to the positions you need through targeted strength work—especially eccentrics and long muscle length training—so the body adapts structurally and neurologically to make those ranges functional.

Call it "mobility training", call it whatever you want, just expose the tissues and joints to enough stress progressively in a safe manner with a large enough stimulus to elicit the adaptations required to gain access to the joint positions you require within your activities and sports.

References / Sources:

Andersen, J. C. (2005). Stretching before and after exercise: effect on muscle soreness and injury risk. Journal of athletic training, 40(3), 218.

Barroso, R., Tricoli, V., dos Santos Gil, S., Ugrinowitsch, C., & Roschel, H. (2012). Maximal strength, number of repetitions, and total volume are differently affected by static-, ballistic-, and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 26(9), 2432-2437.

Bradley, P. S., Olsen, P. D., & Portas, M. D. (2007). The effect of static, ballistic, and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching on vertical jump performance. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 21(1), 223-226.

Caron, T. (2022). Strength Deficit.

Chalker, W. J., Shield, A. J., Opar, D. A., & Keogh, J. W. (2016). Comparisons of eccentric knee flexor strength and asymmetries across elite, sub-elite and school level cricket players. PeerJ, 4, e1594.

Cook, G. (2003). Athletic body in balance. Human Kinetics.

Cook, G. (2011). Movement: Functional Movement Systems. Screening—Assessment—Corrective Strategies. Lotus Publishing

Gary Ward – Creator of Anatomy in Motion

Gordon, A. M., Huxley, A. F., & Julian, F. J. (1966). The variation in isometric tension with sarcomere length in vertebrate muscle fibres. The Journal of physiology, 184(1), 170-192.

Herbert, R. D., & Gabriel, M. (2002). Effects of stretching before and after exercising on muscle soreness and risk of injury: systematic review. Bmj, 325(7362), 468.

Herbert, R. D., de Noronha, M., & Kamper, S. J. (2011). Stretching to prevent or reduce muscle soreness after exercise. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (7).

Huxley, A. F., & Niedergerke, R. (1954). Structural changes in muscle during contraction: interference microscopy of living muscle fibres. Nature, 173(4412), 971-973.

Huxley, H., & Hanson, J. (1954). Changes in the cross-striations of muscle during contraction and stretch and their structural interpretation. Nature, 173(4412), 973-976.

Lima, C. D., Ruas, C. V., Behm, D. G., & Brown, L. E. (2019). Acute effects of stretching on flexibility and performance: a narrative review. Journal of Science in Sport and Exercise, 1(1), 29-37.

Magnusson, S. P. (1998). Passive properties of human skeletal muscle during stretch maneuvers. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 8(2), 65-77.

Marek, S. M., Cramer, J. T., Fincher, A. L., Massey, L. L., Dangelmaier, S. M., Purkayastha, S., ... & Culbertson, J. Y. (2005). Acute effects of static and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching on muscle strength and power output. Journal of athletic training, 40(2), 94.

Orchard, J. W., Kountouris, A., & Sims, K. (2017). Risk factors for hamstring injuries in Australian male professional cricket players. Journal of sport and health science, 6(3), 271-274.

Podcast 117 - Swimming Strength and Speed with Keenan Robinson (Michael Phelps S&C Coach) - Principles of Program Design https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dmcEng2JSUI

Rassier, B., MacIntosh, B., & Herzog, W. (1999). Length dependence of active force production in skeletal muscle. Journal of Applied Physiology, 86(5), 1445–1457.

Sahrmann, S. (2002). Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. St Louis, MO: Mosby.

Shrier, I. (2004). Does stretching improve performance?: a systematic and critical review of the literature. Clinical Journal of sport medicine, 14(5), 267-273.

Steffan Jones – Owner of PaceLab