Mobility in Sport: Beyond Flexibility and Into Function (Part 2: Fight or Flight & Sensory Receptors)

- Dec 15, 2025

- 6 min read

Moving forward in this discussion, I believe it is important to explore why some individuals can access certain joint positions and body shapes far more easily than others. More specifically, what is it about their bodies that enables them to achieve greater ranges of motion within their joints? The short answer is: it depends. But rather than stopping at that rather irritating and lazy response, let’s unpack and examine some of the potential neurological and physiological factors that may explain these differences.

Firstly, let’s consider what I believe to be the most important factor when it comes to “improving range of motion”, which, in my opinion, is often completely overlooked and misunderstood – the role of the nervous system. Now – disclaimer – I am by no means calling myself knowledgeable when it comes to understanding the complexities of the nervous system; this is just my brief and very limited understanding as of now. As survival-driven beings, many of our day-to-day processes are governed by what is commonly known as the “fight or flight” response. This term was first introduced by American physiologist Walter Cannon in his 1915 work, Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage. In it, Cannon described how the body’s sympathetic nervous system equips us to deal with perceived threats – whether by confronting them (fight) or escaping them (flight). Before we progress, you may be wondering what on earth any of this has to do with mobility and range of motion. The link lies in the balance between the sympathetic (fight/flight) and parasympathetic (rest/digest) branches of our autonomic nervous system. When the body perceives a threat – whether from physical danger, emotional stress, or, most likely in line with this blog, certain joint positions – it can increase muscle tone, restrict movement, and limit access to ranges of motion the nervous system deems unsafe.

What Cannon began to outline over a century ago is that “threat” is not limited to immediate, physical danger. The triggers can be subtle and highly individual, shaped by past experience. This idea was further developed for me when I read Bessel van der Kolk’s book, The Body Keeps the Score, which explores how the trauma we endure leaves behind both neurological and physiological scarring. This can manifest as chronic guarding, altered movement patterns, or an unconscious reluctance to explore certain positions – regardless of how much passive range a joint might have. Understanding these concepts allows us to recognise that trauma, such as a torn rotator cuff, and our broader injury history, regardless of how minor some injuries may seem, can have significant long-term implications on our movement. These effects may persist for months or even years after the physical structures have fully healed. Put another way, past pain can lead the brain to associate certain joint positions and ranges with threat or discomfort. In response, it may limit use of the joint in its designed way or reduce the available movement strategies altogether. Ultimately, the brain is highly task-orientated and will find any strategy to complete a given task; however, newly learnt strategies here can have cascading effects on neighbouring segments of the body (which I will discuss later on!).

To highlight this point, a fascinating paper by Hollmann and colleagues (2018) on frozen shoulder demonstrates the relevance and influence of the nervous system on our ability to access certain joint positions. The study involved five individuals suffering with frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis — a condition where the shoulder becomes painful, stiff, and loses range of motion) and examined whether their limitation was due to structural restriction or neurological factors. Frozen shoulder is often assumed to be primarily structural in nature. However, when these individuals were assessed under general anaesthetic, all displayed large increases in shoulder range of motion. This finding suggests that their restriction was largely due to neurological guarding or protective muscle tone. In other words, while awake, the brain may not have perceived it as safe to move the shoulder through its full range; once unconscious, this protective signal was absent, allowing the joint to move more freely.

But this idea can be taken even further. Trauma is not only physical – emotional and psychological experiences can also shape the way we move and hold ourselves. Stress, anxiety, or unresolved trauma can potentially manifest itself in altered breathing patterns and rib cage mechanics as an example. Over time, this can reduce the ability for the thorax to access positions necessary for optimal functionality at the scapulothoracic joint. In turn, this can have a cascading impact on overall shoulder range of motion and performance. So to ignore these connections would be incredibly reductionist. Relating this back to sport, the implications are clear. The positions athletes require within sporting tasks often occur within a fraction of a second. If the nervous system restricts or even prevents certain ranges because of pain history, trauma, or threat perception, the athlete may be forced to use a strategy that could compromise passive tissues, severely limiting performance and longevity. In short, the nervous system is the ultimate gatekeeper of mobility. To improve usable range, we must first understand and, when necessary, retrain how it interprets and responds to perceived threats.

Appreciating Force & Tension – The Role of GTOs & Muscle Spindles

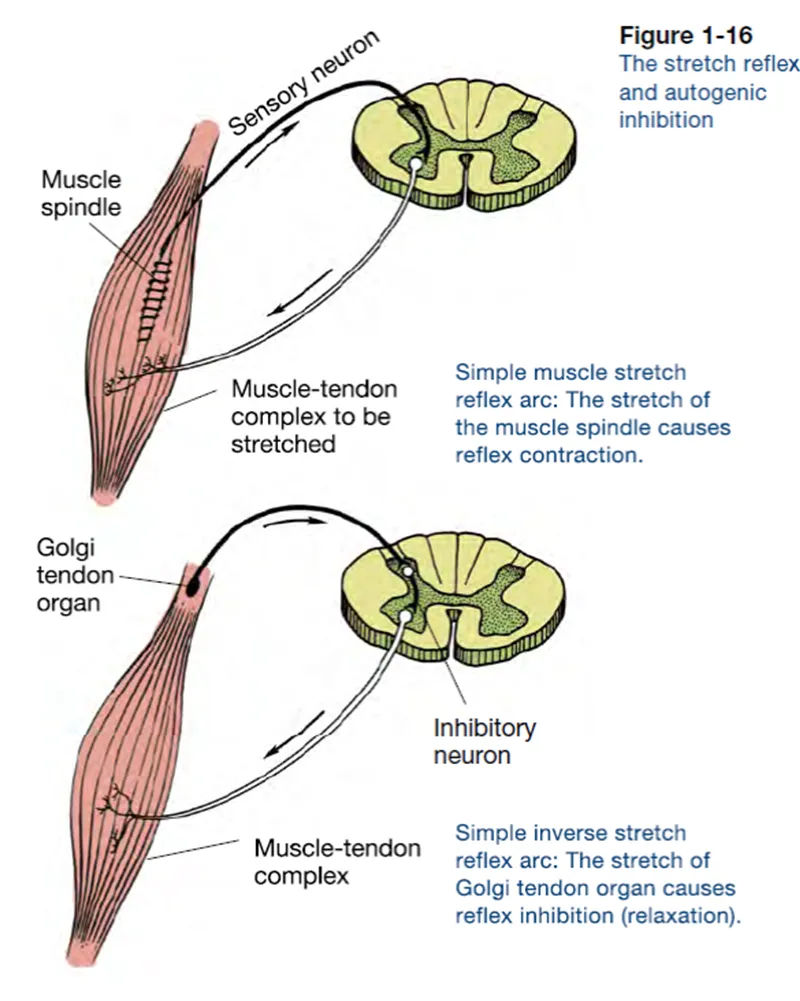

Another potential reason why some individuals can display greater ranges of motion may lie in what are known as our sensory receptors, more specifically how desensitised these receptors are. Now we as humans have a total of three – tendon organs, muscle spindles and joint receptors. However, for the sake of this blog post, I will only be focusing on muscle spindles and tendon organs, more specifically Golgi tendon organs (GTOs).

GTOs are a type of mechanoreceptor that reside within every muscle-tendon junction (MTJ) that detect mechanical changes in muscles. In other words, they detect whether the force or tension within the muscle becomes too high for that specific tissue to tolerate and, through autogenic inhibition, limit muscle activation and force output to prevent overload and injury to protect the muscle-tendon unit (Jones et al., 2004). In practice, this means you may not even be able to access a certain joint position in the first place if the muscle cannot generate the necessary force to control and support the joint position. For example, when performing a heavy barbell back squat and nearing the bottom position, tension rises in the glutes, hamstrings and quads. The nervous system will detect the increased tension within those muscles is about to exceed the tolerance and therefore limit the range of motion, preventing the lifter from dropping any deeper into the squat.

On the other hand, according to Zatsiorsky (1995), muscle spindles are sensory receptors located in parallel with muscle fibres that detect changes in muscle length and the speed of that change. When a muscle is stretched too much and/or too quickly, it triggers a reflex contraction (myotatic reflex) to resist further stretch and return the muscle toward its initial resting length. A real-world example here could be a baseball pitcher rapidly accelerating into maximal external rotation (MER) during the layback of a throw. Here, the muscle spindles detect the rapid, eccentric lengthening of the anterior shoulder tissues (primarily the pectorals and subscapularis) and trigger a reflex contraction, limiting further stretch and protecting the muscle–tendon unit (MTU) from overload.

An appreciation of understanding an individual's exact limitation as to why they are unable to achieve a certain position within an activity is crucial. Differentiating between a neural limitation or simply an inability to produce enough force to enable the muscle to tolerate a specific joint position will require completely different strategies to resolve. Therefore, we need to be asking better questions around why someone cannot access a position; it is no good a tennis player experiencing pain and very limited external rotation during the late cocking/maximal external rotation (MER) phase in a serve and simply prescribing passive/static pec and lat stretching. How do we really know that intervention is tackling the underlying issue as to why that individual cannot access their full MER pain-free? James Jowsey once said, “Stretching and mobilising will not increase [ROM] at heavy loads because the nervous system allows the range it can control,” highlighting how in his specific context the athlete needed to teach the muscles to produce enough force to tolerate the tension in the missing ROMs to enable them to access new positions – funnily enough, passive stretching will never teach muscles to produce force, tolerate tension and velocity as well as build the capacity within muscles to enable greater joint ROM or mobility. So what will? The next part of this blog series will dive deeper into some of the more commonly prescribed interventions, critically evaluating whether or not they achieve what many aclaim they do.

References / Sources:

Cannon, W. B. (1970). Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage: An Account of Recent Researches Into the Function of Emotional Excitement. United States: McGrath Publishing Company.

Hollmann, L., Halaki, M., Kamper, S. J., Haber, M., & Ginn, K. A. (2018). Does muscle guarding play a role in range of motion loss in patients with frozen shoulder?. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, 37, 64-68.

James Jowsey - Strength & Conditioning Coach and Sports Therapist at James Jowsey Training

Jones, D. A., Round, J. M., Haan, A. d. (2004). Skeletal Muscle from Molecules to Movement: A Textbook of Muscle Physiotherapy for Sport, Exercise and Physiotherapy. United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone.

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2015). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. United Kingdom: Penguin Publishing Group.

Zatsiorsky, V. M. (1995). Science and Practice of Strength Training. United States: Human Kinetics.